Big Ideas That Quietly Rewired How We See Ourselves

Most days, life feels personal and local: your job, your street, your feed, your group chat, your bills. Social theory barges in and insists that none of that is only yours, that it’s stitched into systems, incentives, histories, and invisible rules you didn’t vote on. Some of these ideas were born in smoky cafés, some in universities, some in the thick of political upheaval, and plenty of them got misused, oversimplified, or turned into slogans. Still, once a theory lands, it changes what people notice, what they blame, what they excuse, and what they try to fix. Here are twenty that left fingerprints on nearly everything.

1. Social Contract Theory

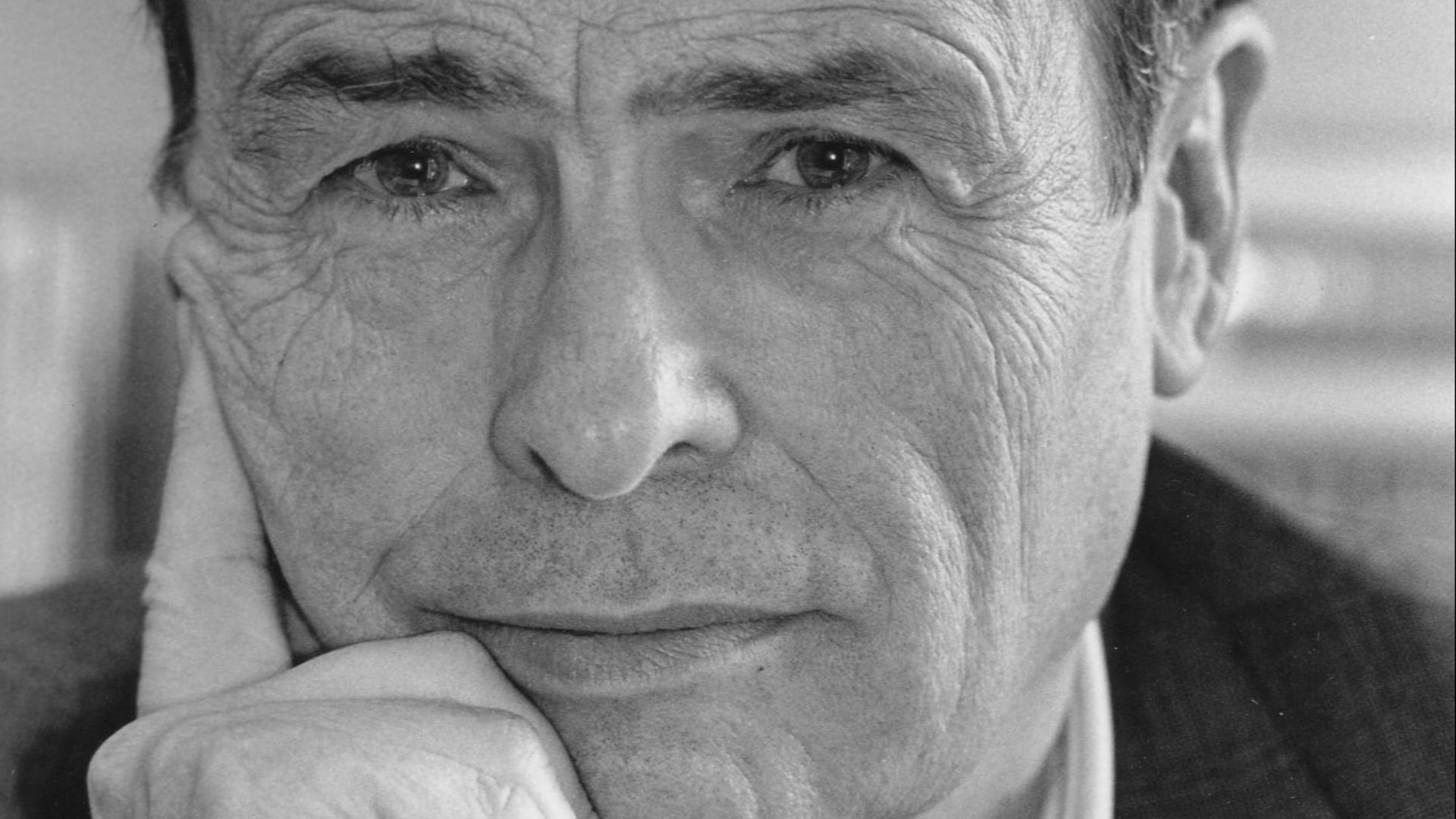

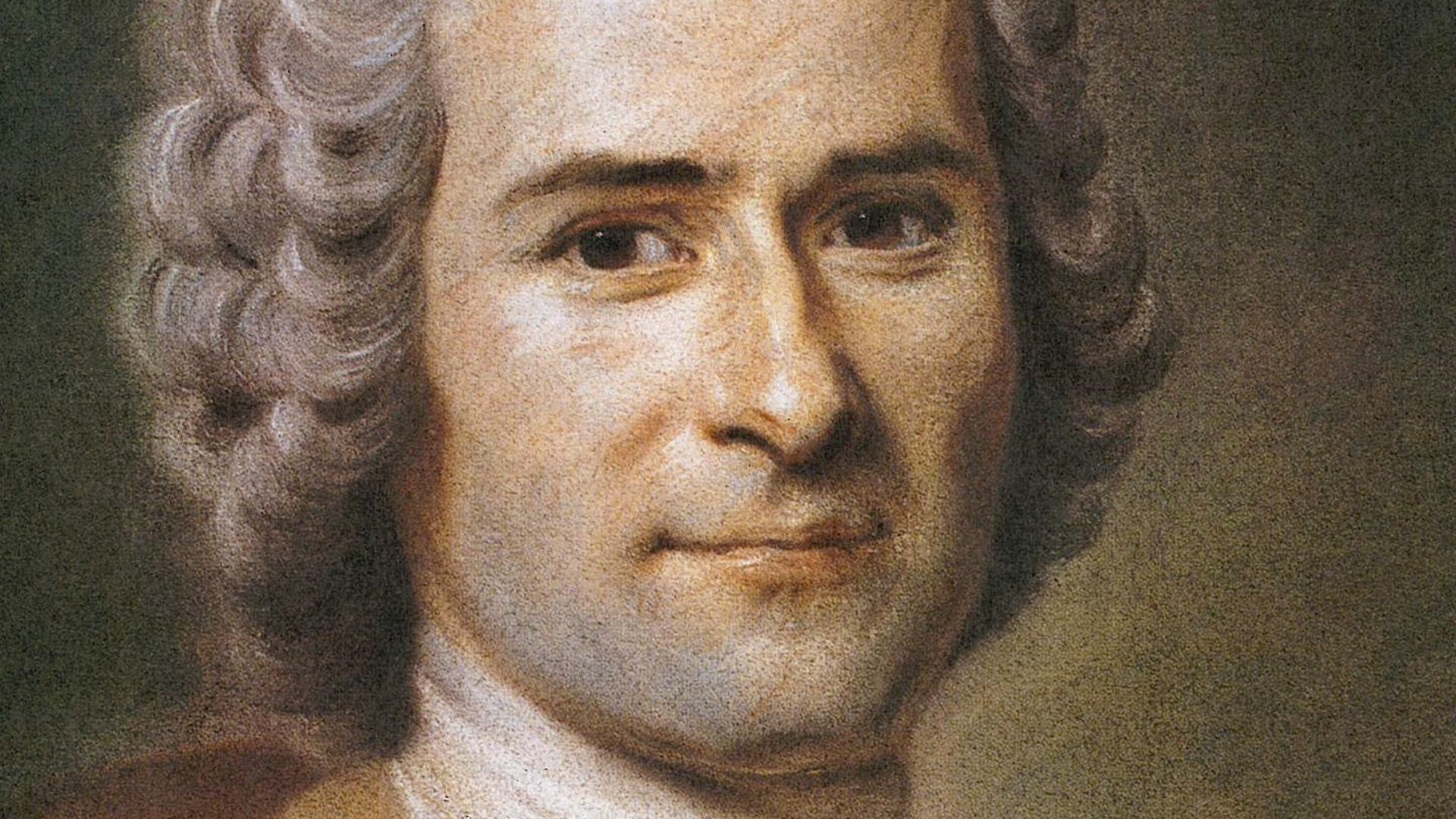

The basic move is bold: legitimate political authority comes from an agreement among people, not divine appointment or inherited right. Thinkers like Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau gave later revolutions a vocabulary for consent, rights, and the idea that government is, at least in theory, replaceable. Even when nobody signs anything, the “we agreed to this” story reshaped what power has to justify.

Maurice Quentin de La Tour on Wikimedia

Maurice Quentin de La Tour on Wikimedia

2. Marx’s Historical Materialism

Karl Marx argued that the engine of history is not great leaders or national myths, but material conditions, labor, and the struggle over resources. That idea turned class into a lens, not just a label, and made exploitation something people could name, analyze, and organize around. The ripple effects hit politics, economics, union movements, and the way ordinary workers started describing their own lives.

John Jabez Edwin Mayall on Wikimedia

John Jabez Edwin Mayall on Wikimedia

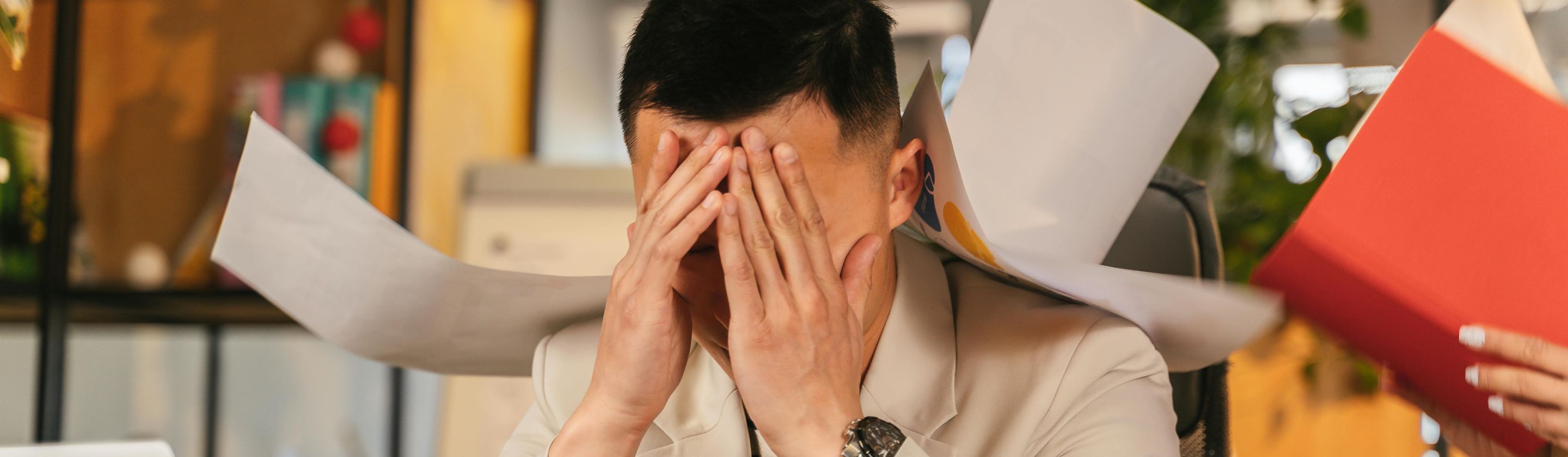

3. Alienation

Marx’s notion of alienation captured a modern ache: the feeling that work can separate people from what they make, from one another, and from themselves. It gave language to the dead-eyed shift, the meaningless metric, the sense of being a replaceable part. Long before people joked about burnout online, alienation was already explaining why productivity can feel like a trap.

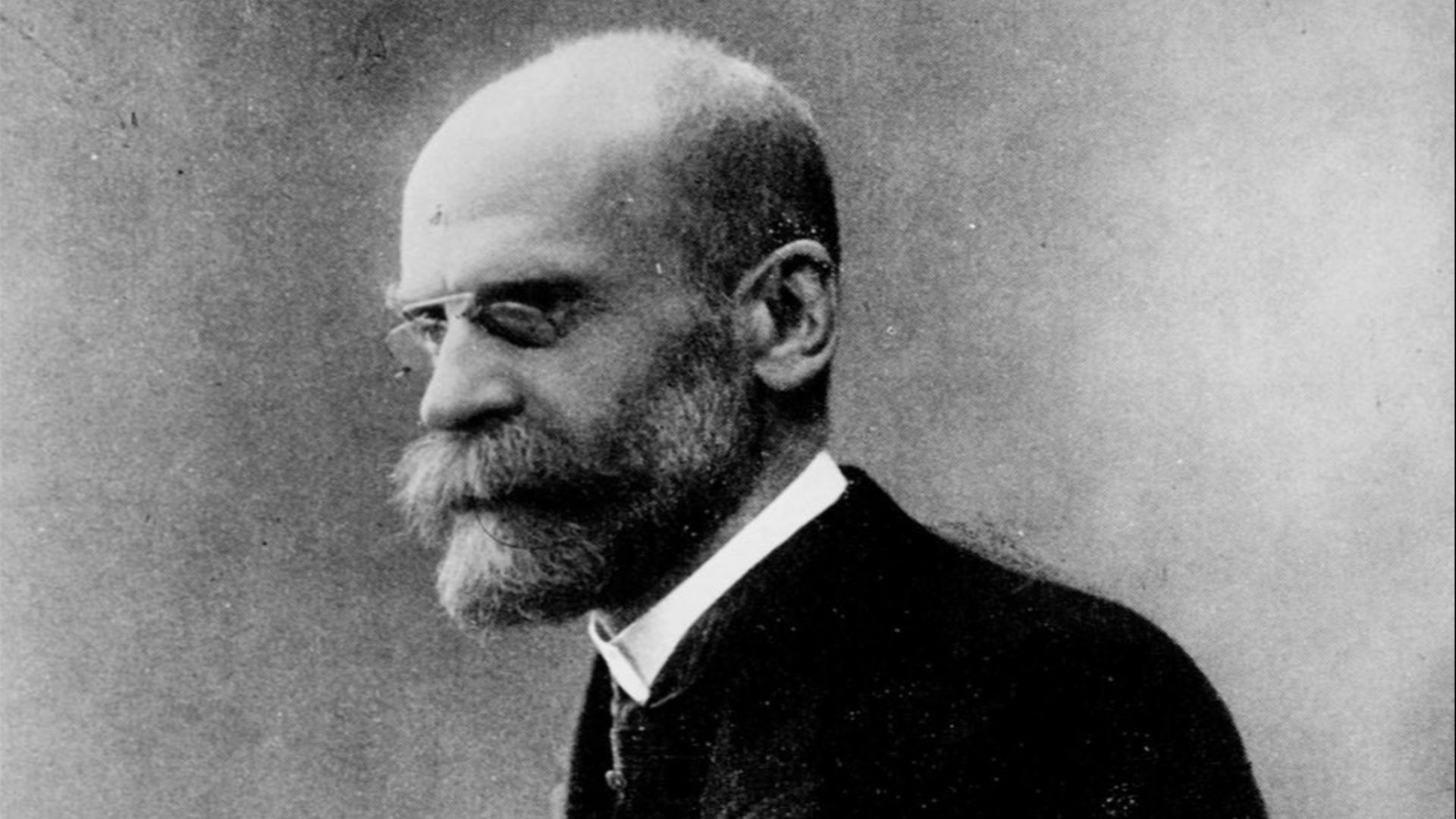

4. Durkheim’s Social Facts

Émile Durkheim insisted that society isn’t just a collection of individuals, it’s a force with its own patterns that shape behavior. Rules, norms, and institutions become “social facts” that press on people whether they like it or not. It’s the backbone of the modern instinct to look for structural causes instead of only personal failure.

Unknown authorUnknown author on Wikimedia

Unknown authorUnknown author on Wikimedia

5. Anomie

Durkheim also described anomie as the disorientation that comes when norms break down and people don’t know what’s expected anymore. It shows up in periods of rapid change, economic shock, or cultural upheaval, when the old scripts stop working. The concept still helps explain why freedom can sometimes feel like floating.

6. Weber’s Rationalization

Max Weber tracked how modern life gets organized around calculation, efficiency, and bureaucratic rules. The world becomes legible, measurable, and optimized, and people become cases, files, and numbers in systems built to run without friction. Even if rationalization brings order, it can also bring that chilly sense of living inside a spreadsheet.

Library of Congress on Unsplash

Library of Congress on Unsplash

7. The Protestant Ethic And The Spirit Of Capitalism

Weber’s famous argument linked certain religious values, like discipline and worldly success, to the rise of capitalist behavior. Whether or not every detail holds in every context, the theory changed how people talk about culture and economics as intertwined rather than separate lanes. It also made “work ethic” feel like a historical product, not a natural personality trait.

8. Symbolic Interactionism

This approach, associated with thinkers like George Herbert Mead and Herbert Blumer, focuses on how people create meaning through interaction. Reality is not only out there, it’s negotiated in gestures, language, and everyday interpretation. It’s a theory that makes a side-eye, a handshake, or a text seen at 2:00 a.m. feel socially consequential.

9. The Looking-Glass Self

Charles Horton Cooley argued that identity forms partly by imagining how others see us. People become mirrors for one another, and the reflected image shapes self-esteem, shame, ambition, and performance. The theory feels almost too obvious now, which is exactly the point: it became part of common sense.

10. Dramaturgy

Erving Goffman described social life as performance, with front-stage and back-stage behavior. People manage impressions, curate versions of themselves, and follow scripts that keep interactions smooth. Once this idea clicks, it’s hard not to see everyday life as a series of small auditions.

Unknown authorUnknown author on Wikimedia

Unknown authorUnknown author on Wikimedia

11. Labeling Theory

This theory, often linked to Howard Becker, argues that deviance is not just an act, but a social process where certain behaviors get defined and punished. Once labeled, people can be pushed into identities they didn’t choose, and institutions can turn a mistake into a life story. It changed criminology, education, and the way society debates punishment versus rehabilitation.

12. Structural Functionalism

Associated with Talcott Parsons and others, structural functionalism treats society as a system of interdependent parts that maintain stability. It can sound tidy, yet it forced people to ask what institutions do, not just what they claim. Even critics use it as a reference point, because arguing with it still requires taking “social systems” seriously.

AnonymousUnknown author on Wikimedia

AnonymousUnknown author on Wikimedia

13. Conflict Theory

Conflict theory flips the focus toward power, inequality, and competition over resources. It’s the idea that social order often reflects who wins, not what’s fair. Once that lens becomes familiar, everything from office politics to housing policy starts looking less neutral.

brewbooks from near Seattle, USA on Wikimedia

brewbooks from near Seattle, USA on Wikimedia

14. Feminist Standpoint Theory

This theory argues that knowledge is shaped by social position, and that marginalized groups can see power structures more clearly because they live with their consequences. It pushed scholarship to treat lived experience as evidence, not distraction. It also changed what counts as a legitimate question in the first place.

15. Intersectionality

Kimberlé Crenshaw’s concept made it harder to talk about oppression as a single-axis problem. Race, gender, class, and other identities intersect in ways that create distinct experiences, not a simple stack of disadvantages. The idea spread far beyond law and academia because it matches what many people recognize in real life.

Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung from Berlin, Deutschland on Wikimedia

Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung from Berlin, Deutschland on Wikimedia

16. Social Constructionism

Social constructionism argues that many things people treat as “natural” are shaped through culture, language, and institutions. It doesn’t mean nothing is real, it means reality is filtered through shared meaning. This theory reshaped debates about gender, mental health, disability, and the stories societies tell about normality.

San Fermin Pamplona - Navarra on Unsplash

San Fermin Pamplona - Navarra on Unsplash

17. Hegemony

Antonio Gramsci described hegemony as the quiet dominance of a worldview that feels like common sense. Power doesn’t always rule by force; it often rules by shaping what seems reasonable, moral, or inevitable. Once people learn the term, they start noticing how consent can be manufactured in plain sight.

Unknown authorUnknown author on Wikimedia

Unknown authorUnknown author on Wikimedia

18. The Panopticon And Disciplinary Power

Michel Foucault used the panopticon as a metaphor for modern surveillance and self-policing. When people might be watched, they often behave as if they are watched, and institutions can shape bodies and habits without direct violence. The theory has aged disturbingly well in a world of cameras, tracking, and performance metrics.

19. Social Capital

Popularized in different ways by Pierre Bourdieu, James Coleman, and Robert Putnam, social capital describes the value embedded in networks, trust, and relationships. It explains why who you know can matter as much as what you know, and why communities with higher trust often function differently. It also made loneliness look like a public issue, not only a private sadness.

20. The Thomas Theorem

W. I. Thomas and Dorothy Swaine Thomas captured a truth that sounds simple and then wrecks naïve realism: if people define situations as real, they are real in their consequences. Perception becomes a social force, shaping behavior, conflict, markets, and panic. It’s why rumors can move crowds, why stereotypes can damage lives, and why narratives can become self-fulfilling.